|

|

|

|

|

{“preview_thumbnail”:”/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/oS7MVsDmTlc.jpg?itok=WOL5yv5a”,”video_url”:”https://youtu.be/oS7MVsDmTlc”,”settings”:{“responsive”:1,”width”:”854″,”height”:”480″,”autoplay”:0},”settings_summary”:[“Embedded Video (Responsive).”]}

This section of the SART Toolkit provides a framework for understanding and maintaining confidentiality in the context of multidisciplinary collaboration.

Confidentiality — the duty to protect victim privacy — is a principle codified in federal [157] and state law, [158] is a stipulation under several sources of federal funding, [159] and is an ethical obligation under professional licensure and certification requirements for some disciplines. [160] While confidentiality has long been understood to be a core tenet (in addition to a legal and ethical duty) of sexual assault advocacy, almost every SART member has one or more confidentiality obligations that govern the way they communicate with other team members and victims.

Whether your SART is newly formed or has been working together for years, confidentiality is one of the more complex issues a team will have to navigate. Some SART members may view confidentiality as an obstacle to effective multidisciplinary collaboration. Confidentiality is just one factor impacting the way multidisciplinary partners work together to ensure a victim-centered, trauma-informed response to sexual assault across systems. With a proper framework in place, SART members will —

Confidentiality is an underlying value of a trauma-informed, victim-centered response to sexual assault. SARTs committed to building such a response must understand both the policy considerations behind confidentiality and the ways in which confidentiality benefits the work of the team and empowers victims.

Maintaining confidentiality supports a victim-centered response. Doing so —

Matters discussed within a SART are not generally protected from subpoena or other court order, even when the team has adopted a confidentiality agreement. Furthermore, a team confidentiality agreement does not release team members from their confidentiality or mandatory reporting obligations under any governing laws, rules, and regulations.

For example, advocacy programs funded through the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) or the Victims of Crime Act (VOCA), require confidentiality regardless of any cooperative or confidentiality agreements that may be in place within a multidisciplinary collaboration. [162] Similarly, HIPAA limits when, how, and with whom a medical professional can share private health information. [163]

All state (and state-funded) agencies, including law enforcement and prosecution, must comply with state data practices statutes, which may limit when and with whom information about a sexual assault investigation or case can be shared. SARTs that engage in case review practices should review with an attorney who specializes in confidentiality the legality of those agreements and policies around information sharing.

SART members should know the differences between privacy, confidentiality, and privilege. Clarity and common language around these terms and definitions will provide a foundation for understanding and respecting the roles and obligations of their team members. For more information on each member’s specific responsibilities, see the SART Membership section of the SART Toolkit.

The following chart [164] provides a general overview of these concepts:

|

PRIVACY |

CONFIDENTIALITY |

PRIVILEGE |

|---|---|---|

|

What is it? A right; a personal choice whether to disclose information. Who holds it? The victim “I decide who knows my information.” |

What is it? The responsibility to protect someone else’s privacy, typically rooted in law or ethics rules. Who holds it? The professional “I have a legal or ethical duty to protect your information.” |

What is it? A legal rule of evidence prohibiting the disclosure of private information against someone’s will. Who holds it? The victim “No one can make you share my information without my permission.” |

Confidentiality is a concern for SARTs when case information is discussed, often during discussions of active cases or case review. Conflict arises when a member’s responsibilities are not understood by all members, there is a perception that team members are withholding information, or a perception that team members are unnecessarily sharing too much information. For the purposes of this discussion, “case information” is defined broadly as any information that is considered private or confidential under federal law, state law, certain funding sources, and/or professional licensure and certification requirements.

Case information can include —

The purpose and function of a SART can impact the way in which team members share and discuss case information, as well as navigate issues of confidentiality. To ensure compliance with the rules and regulations governing confidentiality, SART members should understand in advance when and how the work of the team will involve discussion of case information. Appropriate steps should be taken to empower victims to choose what is being shared, with whom, and with an informed understanding of the potential outcomes.

In general, there are three primary ways in which SARTs engage in discussion of case information, or conduct “case conversations.” [165]

In active case management, SARTs (typically a subset of the full team) engage in a conversation around open cases to ensure coordination leading to the timely and effective victim-centered response and investigation. Conversations may also explore whether all investigatory steps are exhausted, and potential charging options, and generate case-specific ideas and actions to improve the overall response to each case.

Cases that are high-risk — including those where there is a high lethality potential (homicide or homicide-suicide), where the perpetrator is engaged in retaliation, where the perpetrator is moving or otherwise restricting a victim’s access to services, or where minors or children might be at risk — may fall into the category of active case management.

The increased risk of or actual occurrence of physical harm to the victim may create a challenging interpersonal situation between individuals or teams. Increased tension may arise among team members, both those seeking information and those who cannot fully disclose client information. Instances such as this highlight the need for —

SARTs working on active cases should discuss these concerns, specifically, with an attorney specializing in confidentiality obligations.

SARTs engaging in active case management should also be extremely well versed in danger or lethality assessments to increase their ability to monitor dynamic situations. This includes knowledge of strangulation as a health concern and risk factor. Many tools are developed for this purpose, although most research supports that victims are good assessors of their own danger. [166] For more information see the Lethality Assessment section of the SART Toolkit.

Example of Active Case Management:

An investigator was working on a difficult sexual assault case and decided to bring it to the subset of the team that handled active case management. The investigator wanted insight from others on how to proceed when he encountered several challenges and dead ends.

The investigator presented the case facts to the group and identified the difficulties they faced. The prosecutor offered a new strategy and suggested obtaining search warrants for specific pieces of evidence based on what had worked in previous cases. The advocate offered suggestions for ways to support victims during lengthy investigative processes, and the medical professional explained the medical terminology from the sexual assault exam report to the group so that they could better understand its significance.

The advocate and the medical professional who were present had not worked directly with the victim so there was no risk of confidential information being shared. The victim had signed a release of information for the investigator to obtain the exam report as part of the case investigation.

Even in this scenario, identifying information about the victim and suspect was not shared because it was not pertinent to advancing the case. The investigator was able to use the suggestions to continue the investigation and ultimately deliver a stronger case to prosecutors. Additionally, the investigator knew the potential impact of the prolonged case on the victim and could better explain the challenges to the victim while minimizing the risk that the victim would disengage from the process. The strategies learned during this process may have been relevant in future cases.

During case review, SARTs examine closed cases to identify gaps and successes of the systems response, as well as measure the effectiveness of interagency protocols. When done effectively, case review helps a team to identify patterns and gaps that may not have been obvious at the time of the case, and can result in changes in policy, training, procedure, etc. See the case review section of the SART Toolkit for additional information on planning and executing a case review.

Example of Case Review:

Note: In this example, the team decided to obtain signed releases from both the victim and the offender in order to discuss the case among all the service providers present. Getting a release from the offender allowed treatment records to be shared with the team. Including the treatment provider in the discussion enhanced other SART members’ understanding of evaluating offender risk, increasing their ability to recognize risk and discuss safety with victims.

A team decided to review a specific case of intimate partner sexual assault, and sought to include the offender treatment provider in the discussion. The treatment provider conducted training for the SART, and came to meetings on occasion, but was not a formal member of the team.

The case involved a woman and a man who had separated. After the separation, the man broke into the woman’s home and sexually assaulted her. The case was charged and proceeded through the system resulting in a conviction. After sentencing, the case was reviewed by the team as a way to compare the protocol with service delivery to see how the protocol worked. During that review, the team learned that some information known to several responders was not communicated with all team members or with the defendant’s treatment provider.

In reality, the victim had made previous reports and had obtained protective orders citing sexual assault in the past, prior to the charged incident. The team had discussions about where the information was lost and discussed ways to prevent this from happening in the future. It was somewhat surprising to the team to learn there were missed opportunities for intervention, as the team initially viewed this particular case as a success because the case was prosecuted, and the perpetrator was convicted and enrolled in a treatment program.

In addition, the full information about the offender’s frequency of perpetration was not accurately relayed to the treatment provider, who was under the assumption that the assault was an isolated incident, and had made treatment recommendations for the offender based on that information.

This process changed the team’s perspective and illuminated many areas where the system could do more to support victims, hold offenders accountable, and protect communities. The team identified several instances, some small, where they could adjust to enhance service provision and successful outcomes. During this case review, the SART recognized if the system had responded more effectively in the beginning, subsequent acts of violence may have been avoided.

In systems consultation, SARTs are reacting to an emerging systems issue that is impacting the process. Often this is identified when something goes wrong or a protocol is not being followed. Case information may be discussed to identify success, gaps, and strategies to improve the overall response. Often these discussions do not need to include specific case information as the concerns relate to the services provided, not the victim.

For more information, see the Evaluation and Systems Change sections of the SART Toolkit.

Example of Systems Consultation:

Hospital staff report to the director of the local sexual assault advocacy program that there are advocates who routinely fail to respond to the hospital in a timely manner when called to meet with a victim. Although this appears to be a concern specific to a few advocates, the hospital staff and advocacy program work together to understand why the advocates are not arriving in a timely manner. Together, the hospital staff and advocacy program explore questions such as these:

These questions lead teams to identify system-wide concerns and solutions. In this case, the “timely manner” was not clarified in protocol and hospital staff believed it to be a different time than required. The hospital staff worked with the advocacy organization to decide on a timeframe — 30 minutes — that worked for everyone. The advocacy organization and hospital discussed potential challenges to the 30-minute timeframe and, for these rare cases, created a system for the advocate to call and speak with the victim.

Sexual assault is a complex issue requiring the coordination of many systems and professionals, while its human dimension can touch everyone involved in deep ways. In most communities, the members of a SART have ongoing professional and personal contact with one another. Team members may discuss case information outside the SART’s actual scope and purpose. These side conversations may happen because a team member finds it convenient to confer on a case with another member outside of SART meetings.

Discussing case information can help SART members form a bond, develop trust, clarify roles and expectations, and process stress and secondary trauma. However, these benefits should never come at the expense of confidentiality.

Side conversations resulting in a breach of confidentiality put the integrity of the case at risk and can create a chilling effect on victims’ willingness to interact with the system at all.

SARTs should proactively discuss breaches of confidentiality to prevent them as well as to develop a process for handling breaches to confidentiality in a legal and ethical manner.

Examples of Side Conversations:

Practice Tip: These examples illustrate ways your SART can improve confidentiality practices without compromising the benefit of team discussions about system response.

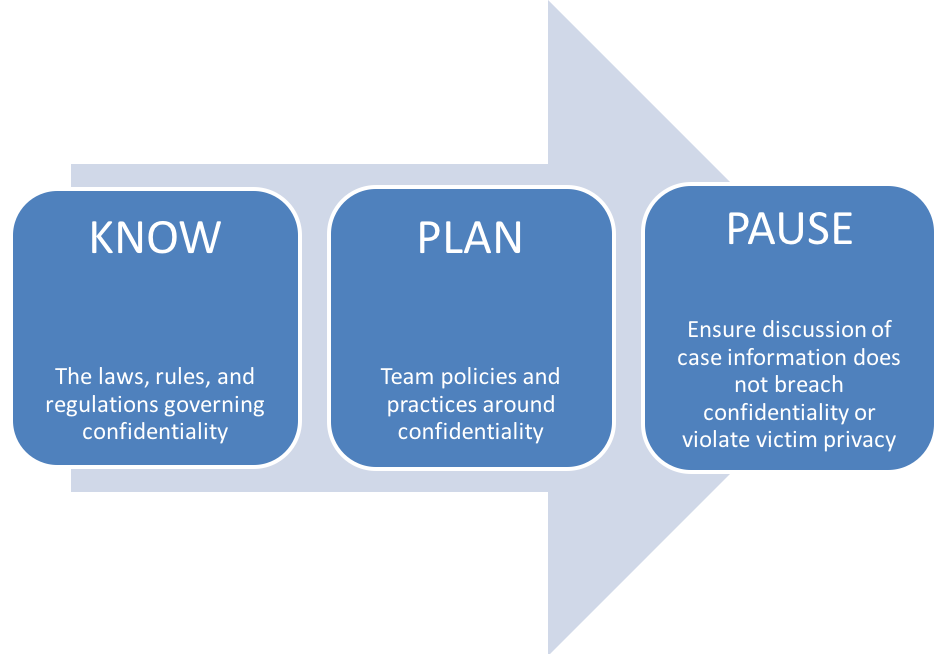

Whether the work of your SART includes active case management, case review, or systems consultation, any time case information is discussed, your members should be alert for potential confidentiality implications.

The framework below can help your SART institutionalize the practice of confidentiality in a way that facilitates multidisciplinary collaboration without breaching confidentiality or violating victim privacy.

A basic, but critical, starting point to handling confidentiality issues to ensure that all team members understand all legal requirements that apply to any discussion of case information.

The following list [168] is not meant to cover all laws related to confidentiality but to provide examples of those that commonly apply to team members. Your SART may have additional regulations and requirements that are not included in the list below. The Victim Rights Law Center’s CCR Toolkit: A Privacy Toolkit for Coordinated Community Response Teams provides a consolidated overview. [169]

Practice Tip: Engage your members in a discussion of the practical implications of complying with the governing laws, rules, and regulations regarding confidentiality. For example, in addition to protecting victim privacy and complying with HIPAA, keeping a victim’s medical information confidential also protects the neutrality of individual SAFEs and SAFE programs. This ensures that the evidence collection expertise will be accepted in court with a minimal level of bias toward the victim or prosecution process.

HIPAA affects SARTs if SARTs share patient information. A common conflict related to HIPAA and caring for sexual assault patients arose from health care facilities concerned that requesting advocacy services from rape crisis centers prior to getting consent from a patient would violate HIPAA. These concerns, focused on victims’ interests, led to valuable conversations that resulted in increased collaboration between advocates and health care providers.

National protocols and existing best practices support calling the local rape crisis center to send an advocate to the hospital without sharing identifying patient information. Once the advocate is at the hospital, the medical provider asks the patient if they would like to meet with the advocate. The patient then has the ability to accept or deny advocacy services. Local protocols have outlined this process in detail to ensure turnover in staff will not affect practice.

In addition to protocols, health care facilities and advocacy agencies can develop and sign Business Associate Agreements outlining what information can be shared by health care providers to rape crisis centers when they call for an advocate. [182] The information that is shared by medical care providers varies by community. SART members can discuss what information may be helpful to share and why that is or is not possible to ensure the best care for the patient.

Your SART should discuss, clarify, and develop processes around any points of service provision related to HIPAA before a complication develops. See how one state addressed issues of HIPAA: The Sexual Assault Task Force in Oregon documented its HIPAA guidelines in its SART Handbook [183] and included a copy of the Authorization to Use and Disclose Protected Health Information.

On an ongoing basis, your SART can discuss HIPAA rules, including misinterpretations. This could include inviting technical assistance providers to present HIPAA-related training for your members or with a health care institution’s legal department.

Your SART can proactively discuss and incorporate HIPAA guidelines into your protocols and trainings to ensure all team members are aware of what information can be shared under what circumstances, what permissions are necessary, and the obligations of medical providers under HIPAA. Unnecessary conflicts can be avoided by ensuring all your members understand how HIPAA affects their work together.

Your SART can plan for HIPAA compliance by discussing and building into your protocols —

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) establishes national standards for the protection of individually identifiable health information created or held by health care providers, health insurance companies, and health clearinghouses. HIPAA was created due to concerns that electronic medical records could be easily disclosed to numerous sources without a patient’s knowledge or consent. Because of this legislation, protection was expanded to all types of health information including electronic, written, or oral. [184]

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published the first HIPAA Privacy Rule in 2000 to ensure individuals’ health information is properly protected while allowing the flow of health information as needed to provide high-quality health care. [185]

HIPAA —

SART members should know and understand the laws that govern confidentiality in the state, tribe or territory where they operate.

Federal, state, or agency money that comes through certain federal funding sources (including the VAWA, VOCA, and FVPSA) restricts the sharing of victims’ private information. For example, recipients of VAWA money must protect victim confidentiality by not releasing Personally identifying information (PII) unless they are required to do so by statute or court order, or a victim allows release of the information in writing.

Most local domestic violence and sexual assault programs receive VAWA and FVPSA funding through OVW grants and the Department of Health and Human Services. Advocacy programs can ask their state’s domestic violence or sexual assault coalition to help determine if they receive VAWA or FVPSA funding.

PII is information that might allow someone to know who a specific victim is, such as name, address, contact information, Social Security number, etc. Your community’s attributes, such as size and particular demographics, can also impact the ability of someone to identify a victim. Particularly in smaller areas, team members should be mindful that seemingly insignificant pieces of information or particular details could disclose a victim’s identity.

Examples of PII:

VAWA, VOCA, and FVPSA require that a victim’s release of information be informed, written, and for a limited duration of time (i.e., the release is valid for a specified number of days after the date signed and a new release is required when the time limit has been exceeded).

Informed consent ensures that the victim fully understands, and that the release indicates —

Consent must be freely given, and services may not be contingent on the victim’s willingness to sign a release. In addition, the victim may change their mind and may revoke the release at any time , verbally or in writing.

Government agencies may also have data privacy rules that dictate certain elements that must be present in a release or how often releases must be obtained.

Practice Tip : It is a best practice for your SART to obtain written releases of information when you anticipate a discussion of case information. Use the “W.I.T.S. Release” as a guide: [189]

Some agency or insurance policies and protocols may also include confidentiality policies. A hospital may have a policy not to discuss cases or release records without a release to be sure that the hospital is in compliance with HIPAA, while other agency or insurance policies may be negotiable. All members of your team should have a clear understanding of the purpose behind each individual agency’s restrictions on discussing cases.

Team members who are licensed or certified professionals should discuss any information-sharing obligations that may accompany their professional status.

Unique confidentiality issues may arise when serving victims who may hold particular identities such as minors, elders, those who identify as LGBTQ, those in educational settings, military victims, incarcerated victims, Native American or indigenous victims, and possibly all who live in rural communities. More information on these populations can be found in the SART Toolkit.

Collaboration with Victim Advocates (PDF, 2 pages)

The International Association of Forensic Nurses’ position statement outlines IAFN’s support of victim advocates at hospitals as an essential member of the multidisciplinary team, with respect to HIPAA. This position statement can be useful to SARTs working with advocates in hospital settings.

Authorization for Disclosure of Health Information (Microsoft Word, 2 pages)

This sample form from OVC can be used to authorize a disclosure of health information so the victim can have a sexual assault advocate present during the medical exam.

Authorization for Release of Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Screening (Microsoft Word, 2 pages)

This sample release by the State of New York allows the victim to give consent for a screening of drug-facilitated sexual assault.

End Violence Against Women International offers an FAQ that provides guidance and links to additional resources.

Mandatory Reporting on Non-Accidental Injuries: A State-by-State Guide (PDF, 51 pages)

This resource by the Victim Rights Law Center provides state-by-state information on mandatory reporting for medical providers and other applicable professionals.

The Health Care Provider’s Guide to the HIPAA Privacy Rule by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services explains when health care providers can share patients’ health information with the patient’s family members, friends, or others.

HHS.gov describes HIPAA’s background, national standards, compliance, and enforcement and provides HIPAA-related links.

HIPAA Basics for Providers: Privacy, Security, and Breach Notification Rules (PDF, 7 pages)

This guide by the Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services introduces HIPAA and HIPAA-related resources.

This website by the National District Attorneys Association describes HIPAA exceptions for law enforcement and social service agencies.

HIPAA: Health Insurance Portability & Accountability Act (PPT, 32 slides)

This presentation from the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape briefly outlines HIPAA.

HIPAA Privacy Guidelines and Sexual Assault Crisis Centers (PDF, 7 pages)

The HIPAA Privacy Guidelines and Sexual Assault Crisis Centers covers the impact of HIPAA privacy guidelines on sexual assault programs, including the use of advocates in emergency departments.

A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examination: Adults/Adolescents (PDF, 144 pages)

The National Protocol for Sexual Assault Medical Forensic Examination provides guidance on HIPAA and describes offering community-based advocacy as best practice.

This glossary lists terms associated with the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Recordkeeping is a complex issue. Nonprofit organizations and government agencies are required to keep certain records by state law, licensure regulation, funding agency, or auditors. Other records are kept for use in grant funding requests, statistical analysis, and evaluating a program’s success.

Often SART members will have a system to collect their own agency data; however, recordkeeping for the SART may be important for reasons such as tracking victims’ experiences and identifying gaps in systems’ responses. Your SART should carefully balance the benefits of recording information against the possible harm that the information could cause the victim or the criminal case if the information were released.

Your SART should consider developing written policies on recordkeeping based on guiding principles. In other words, you should always know why information is being kept (e.g., for funders, for the victim’s benefit, for reference).

These are suggested guidelines for recordkeeping:

There are benefits and burdens to recordkeeping. Making decisions about what to record and what not to record is easier if you have underlying principles to guide the process. [190] The more data you collect, the more you will have to protect. Safety risks will be less if you do not collect data you do not need.

You’ll need to decide —

Nonprofit organizations and government agencies may embrace technology without thoroughly understanding its vulnerability to hacking. As data systems become increasingly interconnected, it is vital that SART organizations anticipate and minimize the potential for harm to victims. Essentially, you need to secure the confidentiality of all communications and minimize any data about victims that are collected, stored, and shared. In addition, because some victims will request assistance or advocacy online, it is critical to think proactively through all safety, confidentiality, and monitoring possibilities relating to electronic communications.

Best practice tip: Many teams shred all copies of documents and notes prior to leaving a case review, keeping only a summary of concerns or action items identified during the discussion.

Your SART should develop policies for electronically stored records, such as the following: [191]

Recently, there has been increased public interest in accessing police data to improve accountability and transparency. Many law enforcement agencies across the United States release police data online in an effort to meet requests for public records and as part of open government initiatives.

For the domestic violence and sexual assault community, police data could help inform the public about how law enforcement responds to and handles these crimes. However, data sets can also be problematic for victims of violence. For example, most of the open data sets publish information about specific crimes that includes, at the very least, the date, time, location (actual location or block address), incident number, and type of crime (domestic violence, assault, rape, etc.) This level of information can be identifying, even if a person’s name is not mentioned, particularly in smaller communities.

Data Security Checklist to Increase Victim Safety and Privacy (PDF, 2 pages)

The Data Security Checklist by National Network to End Domestic Violence (NNEDV) provides guidance for programs or service providers that are developing data collection initiatives.

Frequently Asked Questions on Record Retention and Deletion

NNEDV provides answers to common questions regarding record retention and deletion.

How Law Enforcement Agencies Releasing Open Data Can Protect Victim Privacy and Safety (PDF, 5 pages)

“How Law Enforcement Agencies Releasing Open Data Can Protect Victim Privacy and Safety” by the Police Foundation and NNEDV describes the need for victim privacy to be a central consideration in efforts to share data with the public and includes specific recommendations.

Open Police Data Initiatives: What Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Programs Need to Know (PDF, 5 pages)

The “Open Police Data Initiatives” by NNEDV emphasizes the importance of advocates’ involvement in decisions to release police data online, and includes basic information to support advocates in joining those conversations.

Establishing your SART’s policies and practice is a first step in developing a confidentiality plan.

Once your members know the laws, rules, and regulations that govern confidentiality, as well as the context in which discussion of case information falls within the mission and purpose of your SART, it is important to have a plan in place for navigating situations in which confidentiality may be at issue.

Team policies and practices should be determined in advance of conducting any type of case conversation to proactively protect victim privacy, eliminate confusion around how and when case information will be discussed, and avoid conflict among team members if some members cannot legally or ethically provide information.

Policies and practices may include —

A good strategy for your SART to implement is to anticipate potential “pause button” moments that may arise during the course of the team’s work. Pause button moments are those times where team members should pause to ensure that they are not inadvertently breaching confidentiality before continuing the conversation, whether it is taking place in the context of active case management, case review, systems consultation, or as part of a “side conversation.”

Practice Tip: One way to incorporate confidentiality reminders into the work of your SART is to brainstorm potential scenarios that may constitute a pause moment. By identifying the ways in which confidentiality issues may play out, SART members will be more likely to recognize when they are venturing into compromising territory.

Pause button moments can also include unintentional waivers of confidentiality, such as —

The purpose of this part of the SART Confidentiality Framework is not to prevent or hinder your SART from engaging in case conversations. Rather, it is to provide you with a strategy for effectively collaborating without inadvertently jeopardizing the work of the team through a breach of confidentiality. It requires that team members recognize the need to pause in their discussion of case information to ensure that victim privacy, and other confidential information, is being protected.

1) Does this conversation put victim privacy at risk?

Victim privacy should be a top priority for SARTs who have committed to being victim-centered and trauma-informed. Whenever case information is being discussed, the first question a SART must ask is whether victim privacy is at risk. If the answer to this question is yes, the conversation must be discontinued.

For example, when the work of the team is active case management, team members are coordinating around a specific case to ensure timely and effective processing of that case. The role of community-based advocates on an active case management team is to provide general guidance and advice that will help the team remain victim-centered through the course of the case.

The advocate may not share privileged communications with the rest of the team, even if the advocate believes this will help the victim. However, with the victim’s permission in the form of a written, informed, time-limited release of information, the advocate may share only the specific information permitted by the release with other SART members.

Example of the Risk to Victim Privacy:

SART members are giving agency updates during a monthly meeting, and the prosecutor celebrates a victory in a recent case, crediting earlier improvements made to the interagency protocols. In her enthusiasm, one of the community-based advocates who worked with the victim in that case begins to recap a private conversation she had with the victim during trial, in which the victim shared with the community-based advocate some details that caused her to question whether the prosecutor would win the case.

The community-based advocate simply wants to congratulate the prosecutor on winning a very difficult case. In this example, it was important for the team to celebrate a victory that came about partly because of the work they had done to improve interagency protocols.

However, even though the case was resolved or “closed,” the communications between the victim and the community-based advocate was still privileged. In addition, the details of her conversation with the victim were not relevant to the actual work of the team.

2) Is other confidential information being discussed?

Private information about a victim or communication that a SART member with privilege has had with a victim is not the only information that is governed by laws, rules, and regulations around confidentiality. Even if the case information being discussed does not impact victim privacy, SART members discussing case information should also ensure that other violations of confidentiality are not occurring as a result of the conversation.

Example of Protecting Other Confidential Information:

A SART is engaging in a case file review process to identify areas for improvement when investigators are conducting victim interviews. Team members used the previous month’s meeting to review all applicable laws, rules, and regulations governing confidentiality, and are using a case file review process that adheres to best practice. In addition, the law enforcement agency whose case files are going to be reviewed has taken steps to redact identifying victim information, as well as other confidential information.

3) Does discussion of case information comply with the governing laws, rules, and regulations, as well as team policies, regarding confidentiality?

There are times when the discussion of specific case information does not violate victim privacy, is relevant to the work of the SART, and does comply with confidentiality. When done correctly, these conversations can lead to system-level improvements to the response to sexual assault.

Example of a Case Conversation Done Correctly:

A local SART is engaging in a case review process for the purposes of decreasing the number of “declined to prosecute” cases. While discussing one such case involving the sexual assault of a male victim by his brother-in-law, a prosecution-based victim-witness advocate exclaims, “I remember that case! I spoke to a family member who walked in on the assault, but did not report it to law enforcement because she had just married into the family and was not sure if the sexual contact was consensual. She did not feel comfortable asking her new husband about it, and only briefly brought it up to me when dropping the victim off for a meeting at our offices.”

The prosecutor responded that, had they known this information, they would have likely proceeded with the case. In this example, the information shared was relevant to the work of the SART, which was looking for ways to increase prosecution of sexual assault cases. Furthermore, the victim-witness advocate is a systems-based advocate not bound by the same confidentiality obligations as a community-based advocate, and thus obligated to share information with the prosecutor related to the case and was sharing information she received from a victim’s family member, not the victim himself. This conversation highlighted the need for additional training within the prosecutor’s office for the victim-witness advocate.

4) Can the team achieve its goals without discussing case information?

Your SART may be surprised to find that not all information is necessary to achieving its goals.

For example, when the work of the team involves systems consultation or case review, the team is examining the overall response to sexual assault. Therefore, details such as the name of the investigator can be redacted. Team members may still discuss the actions of the investigator for the purposes of identifying patterns, gaps, and areas in need of improvement within the system’s response, and can avoid turning the conversation into a personnel issue.

Example of Alternative Ways to Achieve Team Goals:

A prosecutor who has received push-back from other SART members for her decision to decline a particular case involving a juvenile victim wants the SART to review that specific case in order to help team members understand how charging decisions are made. Rather than open an actual file, the prosecutor can make a presentation to SART members outlining the decision-making process her office uses to determine whether a case involving a juvenile victim should be charged.

CCR Toolkit: A Privacy Toolkit for Coordinated Community Response Teams (PDF, 24 pages)

This CCR Toolkit developed by the Victim Rights Law Center (VRCLC) discusses federal and state laws regarding privacy and information sharing for coordinated community response teams, a privacy checklist, resources, and other information.

A Comparison of Three Approaches to Case Conversations (PDF, 1 page)

This chart from What Can We Talk About? A Guidebook for How Sexual Assault Response Teams Discuss Sexual Assault Cases by the Sexual Violence Justice Institute at Minnesota Coalition Against Sexual Assault details the differences and similarities between systems consultation, case review, and active case management.

The Confidentiality Institute provides up-to-date, state-specific, sophisticated training, toolkits, and on-call technical assistance to help an agency handle its most significant confidentiality and privacy challenges.

Safeguarding Victim Privacy in a Digital World: Ethical Considerations for Prosecutors (multimedia, 60:56)

This “Safeguarding Victim Privacy in a Digital World” webinar discusses ethical considerations using hypothetical examples.

Technology & Confidentiality Toolkit

The Technology & Confidentiality Toolkit was created by NNEDV to assist nonprofit victim service organizations and programs, co-located partnerships, coordinated community response teams, and innovative partnerships of victim service providers working to address domestic and dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking. This toolkit is meant to help providers and agencies understand and follow the confidentiality obligations mandated by the funding they receive through the VAWA, FVPSA, VOCA, and related state and federal privacy laws.

The Victim Rights Law Center provides free, comprehensive legal services for sexual assault victims with legal issues in Massachusetts and Oregon in the areas of privacy, safety, housing, education, employment, immigration, and financial stability. What they learn from representing individual victims is used to train thousands of advocates, attorneys, campus administrators, medical professionals, law enforcement, military personnel, and other professionals throughout the United States and U.S. territories to improve the response to sexual violence.

| Back | Index | Next |